See The Boston Globe for the full article: https://www.bostonglobe.com/2025/06/05/metro/ri-child-care-day-care-funding-pre-k-governor-mckee or download a copy of the article

Even as pre-K expands, child-care centers say it’s more and more difficult to staff infant and toddler rooms

By Steph Machado Globe Staff,Updated June 5, 2025, 5:55 a.m..

PROVIDENCE — Three months ago, Minerva Waldron made an excruciating decision. She closed the only two infant rooms at her daycare center, eliminating care for those under 18 months.

“I felt horrible,” said Waldron, the owner of Over the Rainbow Learning Center. She knew families would be left in the lurch. But the infant classrooms “weren’t even breaking even,“ she said, as state subsidies for children whose families qualify for assistance don’t fully cover the cost.

“It’s just too expensive to run it,” said Waldron. “We had teachers leaving us for Walmart because they’re getting paid more there.”

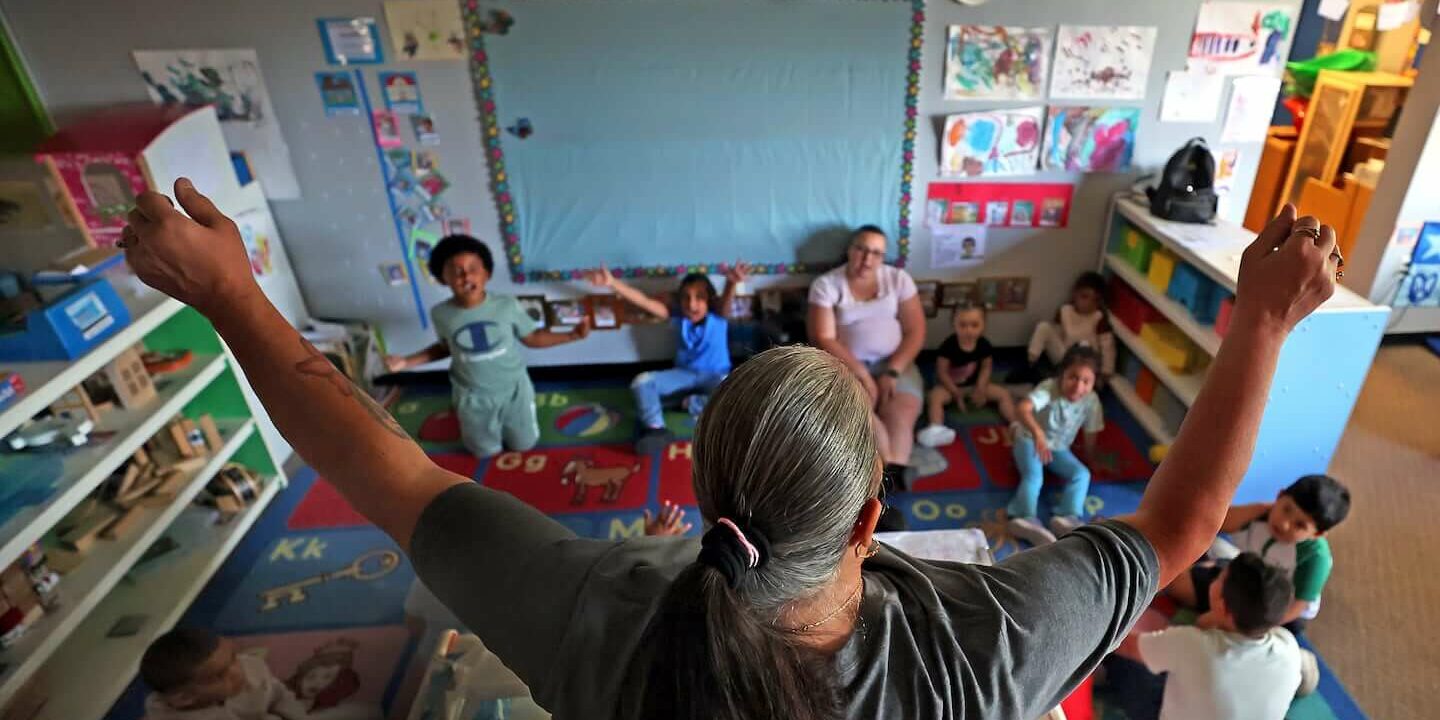

The math to provide infant child care is difficult across the country, as baby-to-teacher ratios are much smaller than preschoolers. Teachers for infants and toddlers make scant above minimum wage, but raising their pay means increasing already sky-high tuition rates for parents. Meanwhile, public pre-K is expanding, offering better salaries for the already-limited pool of early educators.

It’s an unintended consequence of Rhode Island’s pre-K expansion, said Leanne Barrett, the director of early childhood policy at Rhode Island Kids Count. The state’s free public pre-K program has grown by 500 seats in the past three years to 2,800, with a goal of reaching 5,000 seats by 2028.

“A lot of the program facilities and the teachers just move to 3- and 4-year-olds, and there’s nothing left for infants and toddlers,” Barrett said.

Ellen Piangerelli was six months pregnant when she found out Over the Rainbow was planning to close its two infant classrooms. She had sent her older son there through preschool, found it to be “safe and loving,” and planned to send her daughter there after maternity leave.

“It was pretty daunting,” said Piangerelli, who gave birth in February. She realized prices had increased exponentially since she last had a baby four years ago. Many waiting lists were too long to bother joining, since they far exceeded her return-to-work date.

Piangerelli eventually secured a child-care placement in March, two months before she needed to go back to work. Her daughter started last week. “I’m definitely paying more than is comfortable for me to be paying,” she said.

The state’s pre-K expansion plan in 2022 recommended a “set-aside” for infant and toddler care, aimed at preventing the further deterioration of the sector, which has been struggling with teacher retention and long waitlists. The recommendation is based on other states that have expanded pre-K.

Last year, when state leaders funneled an additional $7 million into public pre-K, for a total of $30 million, the Rhode Island Department of Education transferred about $1 million of that to the Department of Human Services for infant and toddler care.

The $1 million was put into a program called Step Up to Wage$ that boosts pay for infant and toddler teachers who make less than $23 an hour.

But that set-aside is not in the budget this year. Governor Dan McKee decreased the early education aid by $1 million compared to last year, funding state pre-K at $29 million but without a transfer to DHS for infant and toddler care.

“Given the limited resources projected for FY26, the governor’s recommended budget prioritized pre-K investments and as such did not include a set-aside,” said Olivia DaRocha, McKee’s press secretary.

She said McKee decreased the total funding for early education this year because fewer classrooms opened last year than projected. A “very small increase” to the number of pre-K seats is expected over the next year, as the state works to help private preschools “meet the rigorous standards” to be approved for state funding.

Child-care advocates are pushing to bring back the $1 million set-aside, warning that infant and toddler classrooms could continue to close if it isn’t restored. They are also asking lawmakers for a permanent change, ensuring that 30 percent of early education money goes toward infants and toddler care, with 70 percent allocated for pre-K.

“The money is absolutely needed, just like the money for 3- and 4-year-olds is needed,” Barrett said. The bill for the 30 percent set-aside has passed the Senate, but not the House.

It’s not immediately clear how many infant and toddler classrooms have had to close or shrink as a result of the staffing crunch. While the state licenses 7,000 infant and toddler seats, they do not track if the child-care centers are using all of their allowed capacity.

For example, at Dr. Day Care, which has several centers throughout the state, CEO Amy Vogel said there are 699 licensed seats but 570 children enrolled, leaving nearly 20 percent of the seats unused because of lack of staff.

The wage boost program has helped 271 child-care teachers so far, DHS spokesperson James Beardsworth said. The state money, which runs out June 30, was added to an existing $1 million in annual federal funding, which is slated to end next year. It’s not clear if the program will continue after that.

The House Finance Committee could release an amended version of McKee’s budget as soon as next week.

“All budget items are still under consideration as the House works to finalize a revised budget,” House Speaker Joseph Shekarchi said in a statement. “But it’s a very challenging year and there is an ever-growing list of requests from stakeholders concerned with the governor’s original proposal.”

Pamela Verklan, chief of philanthropy at the nonprofit Children’s Friend, painted a stark picture of the child care outlook to legislators last month. She said the organization has 100 children on the infant and toddler waitlist — “not due to a lack of space, but because we do not have enough staff to meet the demand.”

“Early educators are leaving the field in droves because they cannot survive on poverty wages,” Verklan told the House Finance Committee.

Lawmakers took issue with the state’s decision to transfer the pre-K money to infant and toddler care.

“It concerns me that it was done without General Assembly approval,” said Representative Scott Slater, the chair of the Finance Subcommittee on Education. “We’re supposed to authorize the spending.” He told the Globe he supports the concept of more funding for child care, if it can be found in the budget.

Waldron said at Over the Rainbow, the infant and toddler teachers make $15-$16 per hour, while preschool teachers can make double that when accounting for the 10-month school year.

Her center has benefited from the state’s pre-K expansion. But the money from the state’s pre-K program can only be used for those seats.

“They keep opening classrooms for pre-K, but what about the little ones?” Waldron said. “Can they get a little something?”

Vogel said the infant rooms will “always be in the red” unless parents are charged an “exorbitant” amount more.

The child-care center is struggling to fill a toddler teacher job posting that has been open for a year. Meanwhile, families are on a waitlist that goes into 2026.

“We need to pay all teachers in early childhood education more money,” she said.

Verklan told the lawmakers their decision is about more than just the budget.

“If we do not act now, the cost socially, economically, and developmentally will be far greater in the future,” she said.

Steph Machado can be reached at steph.machado@globe.com. Follow her @StephMachado.